In the summer of 2017, the Oklahoma City Museum of Art hosted Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic, a mid-career survey for an artist whose stature would grow exponentially one year later with the unveiling of his presidential portrait of Barack Obama. Organized by the Brooklyn Museum, with loans from all of the other host institutions except OKCMOA, its final stop, A New Republic reimagined the museum experience with persons of color replacing white subjects through a series of old master-inspired portraits. Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic’s contribution was to invite a larger segment of visitors to see themselves on the walls of the museum, something that Wiley himself was not able to do growing up.

As a special exhibition, Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic succeeded in creating a new museum experience—one that invited new audiences to identify with the subjects of the paintings, not only thanks to the color of flesh tones that Wiley painted, but also through the clothing and even attitudes of his contemporary sitters. A New Republic was an experience of now, of seeing our world filling the galleries, which in the case of OKCMOA, spread across two floors.

And then, the exhibition was gone, and the faces occupying the Museum’s walls were again mostly those of white Americans and Europeans of the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries; they were people familiar to the Museum’s audience, and the artists who created these likenesses, names like Charles Willson Peale, Thomas Lawrence, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and George Bellows, were certainly as deserving of the honor of decorating the Museum’s galleries as was Wiley. Nonetheless, the same gap that the exhibition first addressed, the same absence that it sought to rectify for three months, had returned with A New Republic’s departure. This, in the end, would be the genesis of the Museum’s purchase of its own Wiley, Jacob de Graeff (2018), more than a year after the exhibition.

Backing up, it was clear before the exhibition was over that we needed to acquire a Wiley. After all, if the Museum believed in the project of the exhibition—to create a museum experience that invited a greater number of visitors, especially those historically excluded due to the color of their skin, to identify with the paintings’ subjects—then we would need a work like Wiley’s to step into permanent dialogue with our existing collection of portraiture. While opportunities to acquire one of his paintings would materialize almost immediately, it was equally important from the start for OKCMOA to acquire the right Wiley, to find the work that would fit best with its existing collection and that would truly stand out most among the artist’s body of work. We wanted the right Wiley again, but we also wanted the best Wiley available.

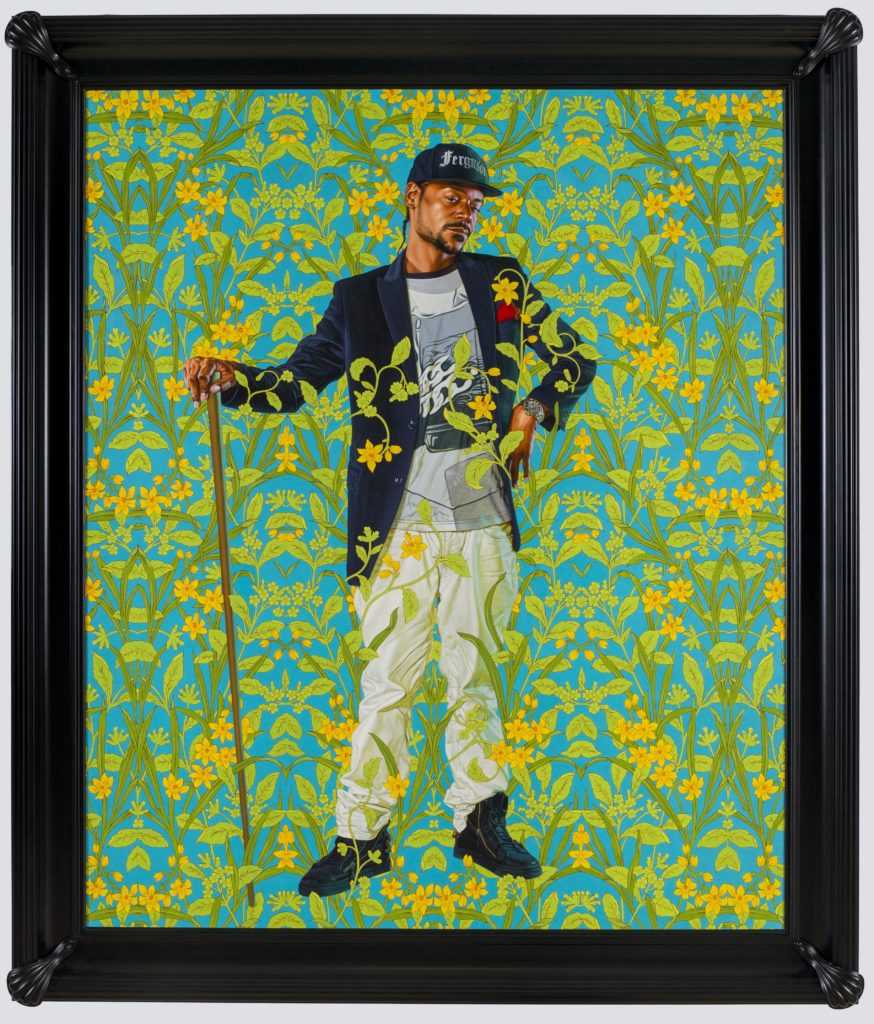

The piece that would fulfill both of these criteria came to our attention in the fall of 2018. Named for the seventeenth-century Dutch politician and nobleman who provided the subject for a painting in the Saint Louis Art Museum’s permanent collection, Jacob de Graeff presents Brincel Kape’li Wiggins, Jr., a Missouri-based rapper whom Wiley found while street casting in Ferguson. Wearing the name of that community, best known for the tragic killing of unarmed African American teenager Michael Brown and the subsequent civil unrest, on his ball cap, Wiggins meets the viewer’s gaze with confidence, his head tilted to the side as his right hand rests on a cane, and his left arm bends to a v as the outside of his left hand falls against his velvet jacket. Wiggins’ clothing provides the most distinctive marker of the piece’s contemporariness, as he likewise sports a graphic t-shirt, baggy white jeans, and black high-top sneakers.

The full-length Jacob de Graeff is a burst of the present-day as it converses with the above objects and others in the Museum’s portrait galleries. Its impact is heightened by its comparatively large format, and at the moment, focal location—the Museum’s current portrait gallery was organized around the Wiley—that brings other works into its orbit. In this way and again in the color of flesh tones rendered by the artist, it is an extension of the legacy of A New Republic, a fulfillment of Wiley’s project of democratizing the act of identification in the space of the museum. It also represents a new, more political path for the artist in its reference to Ferguson, one that gestures towards injustices that extend beyond the under-representation of black and brown faces in the traditional fine arts museum.

In the spring following the Wiley exhibition, a second, single-artist show brought something equally novel and exciting to the Museum’s galleries. Apichatpong Weerasethakul: The Serenity of Madness was the first exhibition in the Museum’s history to predominately feature video work, showcasing moving image art from international art-house giant Apichatpong’s beginnings as an experimental filmmaker in the early 1990s, through to his then most recent interventions into in-gallery film practice (such as 2016’s twin-projector tour-de-force, Invisibility). Though the Museum’s 2014 survey of contemporary Chinese art, My Generation, and again A New Republic (with Smile, my favorite piece in the survey) featured videos as central or key components of their artists’ practice, The Serenity of Madness charted the career of a film and video artist—and one of the world’s most significant moving image artists at that.

Indeed, the idea of acquiring an Apichatong video for the collection was just as automatic as adding a Kehinde to the collection, though not exactly to address an absence—although the filmmaker’s profile as a queer Thai artist does suggest the further positive of adding an under-represented voice to the collection. Rather, the addition of the Apichatpong was meant to bolster the Museum’s new collection of video art, which had been inaugurated about a year before with the purchase of Andy Goldsworthy’s Hedge Crawl… (2012).

The filmmaker and video artist’s 2014 short Fireworks (Archives) was one of the absolute highlights of The Serenity of Madness, thanks both to its spectacular presentation on two hanging panels of glass, and also due to the purity of its form and discourse. Fireworks (Archives) largely follows two of the filmmaker’s more recognizable actors as they traverse a Thai cemetery, illuminating a series of folk animal sculptures as they light pyrotechnics and operate camera flashes in the enveloping darkness.

What results is a pure description of moving image art: light, movement, and sound create meaning, bringing an uncanny world into existence through the most limited of means—and those, moreover, which properly summarize film and video art’s nature as a medium of expression. It is appropriate and indeed intentional that in this, the second of the Museum’s video art pieces—the Museum purchased one of six licenses of the Apichatpong for permanent display—we experience a distillation of moving image art to its essence.

Of course, this purchase was equally intent on making the case for this art in the first place, that the moving image represents one of the most significant interventions into and directions for contemporary art. It is impossible to tell the story of art in our time, a story that the Museum wants to help tell and to which Wiley also adds significantly, without including the moving image. And there are few twenty-first-century artists anywhere in the world who have made a more meaningful contribution to our understanding of what art is (and what it can be) than Thailand’s greatest filmmaker. Fireworks (Archives), no less than Jacob de Graeff, is an art of today.

The third of the Museum’s most transformative recent purchases shares very little with the first two. Ultimately more a matter of opportunity than the other two acquisitions, An Italian Autumn (ca. 1844-47) was discovered in a New York art gallery, following a series of personal referrals, at the end of a long day of gallery visits in December 2018. Although Cole certainly factored in the Museum’s collection plan, our best hope was for a smaller, admittedly less representative landscape—not this beautiful depiction of a fantastical Italian countryside that instantly placed among the permanent collection’s select number of highlights.

An Italian Autumn (ca. 1844-47) is one of two identical painted versions of the same subject by the so-called “founder” of the Hudson River School, Thomas Cole. As the theory goes, Cole presumably painted the second version of An Italian Autumn after a visitor to his studio saw the original and ordered another copy. Whatever the sequence—there really is no way to say whether OKCMOA’s or the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston’s version was painted first—the existence of two identical paintings speaks to something that is all too easy to look past, especially when thinking of landscapes rather than portraits: namely, that paintings are frequently made for commercial reasons, out of a desire to sell a product rather than exclusively from some place of pure artistic inspiration.

Not that An Italian Autumn—and here I am speaking of both versions interchangeably—lacks for the latter. Drawing on a small oil-on-canvas sketch, The Ruins (1831-32), which the artist produced during his time in Italy in the early 1830s, An Italian Autumn synthesizes certain concerns that become more prominent in the “The Course of Empire” series (1833-36) that Cole produced in the midst of Andrew Jackson’s presidency (whom he fiercely opposed). In the Museum’s and Boston’s later set of paintings, we see a composite of stages of civilization, from the ruins that appeared in The Course of Empire – Desolation (1836) to the farmer and livestock of The Course of Empire – The Arcadian or Pastoral State (1834).

In other words, An Italian Autumn represents the rebirth of civilization, an appropriate sequel to “The Course of Empire” and its cyclical view of history. Civilizations rise and fall, yes; but they also rise again, which here we bear witness to in some fantastical corner of Italy—a nation that Cole believe represented the pinnacle of human achievement. With its kneeling religious pilgrim occupying a small corner of the poetic landscape, it is, as an object of rebirth and hope (not least through the touch of sunlight peaking just above the horizon), ideally suited to the just-past Easter season. It is also, somehow, one of the collection’s best suited to speak to our own moment, not the least for its depiction of a devastated Italian landscape. Devastated, but one that is being reborn, which is showing new life and a way forward after a civilization’s inevitable collapse.

-Michael J. Anderson, PhD, President & CEO

The Museum relies on admission revenue from our galleries and films as well as donations to provide rich cultural and educational experiences for all. Please consider making a gift of any size to support the Museum as our community continues to shelter in place.