Never underestimate the power of museums to transform young lives.

My favorite example of this phenomenon is also the story of my late colleague and best friend. Some twenty-five years ago at a conference, I met William Siegmann. I was a curator at a smallish museum with a respectable collection of African art. Bill was the highly respected curator of African and Oceanic art at the Brooklyn Museum. We became fast friends.

Over the years, I spent countless hours traveling with Bill and spending time in his art-and book-filled apartment in Park Slope, Brooklyn. Together, we visited museums, galleries, met with dealers, and argued about art. Bill was more than just a curator; he belonged to that generation of connoisseurs who assembled impressive personal collections while simultaneously scoring significant acquisitions for their institutions. He was also an exuberant host and a gifted cook. His dinner parties were legendary, and he took great delight in seating me next to someone who was my ideological polar opposite simply to watch the sparks fly.

Bill grew up in Minneapolis, and it was he who introduced me to the Minnesota State Fair—an event I have described as the “great gathering of the Minnesota diaspora.” On one of those long, state fair weekends, Bill and I visited his favorite Twin Cities landmarks—his childhood home, Ingebretsen’s Market and the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

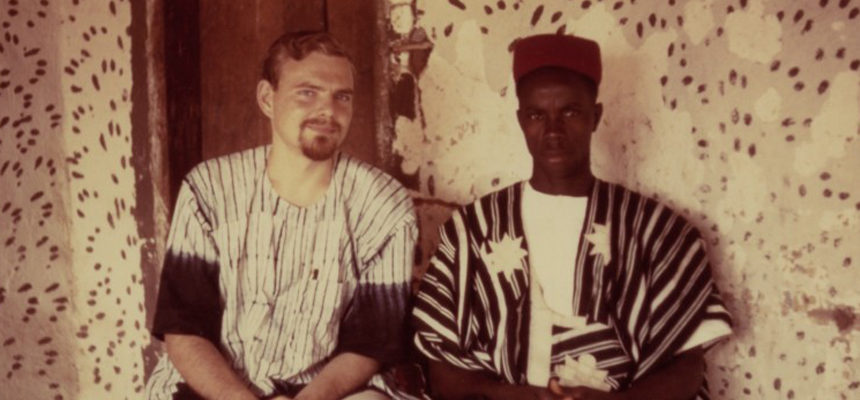

While walking through that museum’s impressive galleries, Bill talked about his life—the introduction to his beloved Liberia through the Peace Corps, his curatorial posts in Africa, San Francisco, and New York, and his numerous friends and colleagues. But mostly, Bill talked about the Minneapolis Institute of Art and its profound effect on him—a middle-class, Midwestern boy of German-Lutheran heritage.

In particular, the Chinese galleries opened his eyes to a world beyond the Midwest. These and other works of art inspired a lifetime of intellectual curiosity and collecting. During that weekend we also talked openly about the future—Bill had been diagnosed with prostate cancer a few years earlier, and he knew his time was limited. He wanted his collection to go to the museum that had such a transformative effect upon him as a boy.

Upon his death in 2011, his personal collection was donated to a number of institutions, among them the National Museum of African Art and my former museum. However, the very best of his collection—the objects he loved most—came home to Minneapolis. Bill’s great gifts are now in the galleries he loved as a child—waiting to inspire a new generation of young people with the wonderment of the great world beyond.

I hope there is much within our own Museum that is inspiring to—and perhaps even transforming—you and your children. Art transports us to other lands … long before we might have the opportunity to visit those places in real life.

Here’s to discovery.