Great works of art have the power to transport us to another time and place. In particular, ancient art is imbued with the cosmological and political codes of societies long vanished, rendering—to modern eyes, at least—objects that are exotic and mysterious.

The same can be true of contemporary art. If we spend time contemplating great works, they may reveal a different, deeper meaning than the one on the surface. This was my great takeaway from a recent New York City visit. While there were a number of art stops on my itinerary, two exhibitions were at the top of my list—Lost Kindgoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia, 5th to 8th Century and Kara Walker’s monumental installation: A Subtlety, or The Marvelous Sugar Baby.

South Asia, probably Sri Lanka

Bronze

Photograph courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

www.metmuseum.org

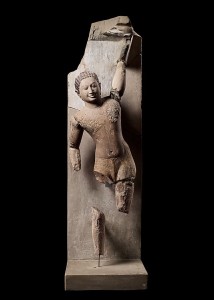

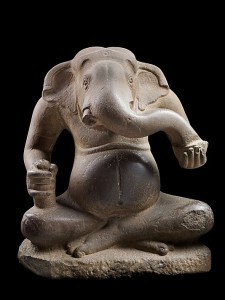

Southern Cambodia

Sandstone

Photograph courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

www.metmuseum.org

Lost Kingdoms, on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 27, examines the powerful sway of India on Southeast Asia during the mid- to late first millennium CE. Showcasing exquisite and powerful sculptures—many of which have never been seen outside their countries of origin—this is the kind of sweeping exhibition only the Met can pull off. Both Hinduism and Buddhism were Indian exports—spread along ancient and extensive trade routes. The competition between—and blending of—these ideologies resulted in some highly original works of art.

Among the highlights for me was this sandstone sculpture from Cambodia. Ganesha is an elephant-headed, pot-bellied deity whose ancient origins relate to fertility and agriculture and who remains a familiar member of the Hindu pantheon.

I was likewise enchanted with a bronze footed bowl with a relief scene of the courtly life of ancient India.

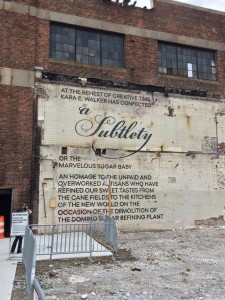

Kara Walker is not someone given to subtlety. This African-American artist is best known for her graphic cut-paper silhouettes depicting slavery in all its brutality. So the title of her monumental sugar creation staged in an abandoned Domino sugar factory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn (and recently closed), is something of a conundrum.

But, as this review in The New York Times describes, the title Subtlety refers to the elaborate sugar creations that were the centerpieces of medieval feasts. The full subtitle, The Marvelous Sugar Baby, an homage to the unpaid and overworked artisans who have refined our sweet tastes from the cane fields to the kitchens of the New World, sets the stage for the complex messages conveyed in her work.

Upon walking into the vast, derelict Domino factory, I was overwhelmed by the odor of burned sugar and the sight of molasses still dripping from the walls. Seemingly whimsical figures resembling blackamoors—those seventeenth to nineteenth century sculptures of Africans incorporated into candelabra or used as supports for tables and plant stands—greeted us. Any notion of whimsy quickly evaporated when I realized these figures depicted children and that the torturous labor of harvesting and refining sugar cane was not limited to enslaved adults.

At the end of this cavernous space was Walker’s monumental sugar sculpture—a recumbent sphinx with the head of a proud and defiant mammy. The Marvelous Sugar Baby has a core of polystyrene and is topped with 160,000 pounds of sugar, donated by Domino. That this mammy is white is an example of the tension for which Kara Walker is known for. In ancient Greek mythology, the sphinx was a ferocious guardian who allowed safe passage only to those who successfully answered a riddle. Kara Walker’s Marvelous Sugar Baby is just as powerful and equally mysterious. I hope you will discover wonder and mystery each time you visit your Museum. There are layers upon layers waiting to be uncovered.