As OKCMOA continues its virtual experience, every Wednesday we’ll take an in-depth look at selections from the Museum’s collection and exhibitions. This week, we’re highlighting the lives and art of four incredible artists from our collection in celebration of Women’s History Month.

The first artist we’d like to highlight is New York City-born painter Yvonne Twining (1907-2004), whose work is featured in our exhibition Renewing the American Spirit: The Art of the Great Depression. As a child, Twining lived in England for several years, but after her father’s death, she and her mother eventually settled in the village of South Egremont, Massachusetts, in 1923. While there, Twining studied with two Impressionist painters before moving to New York City to train at the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League in the latter half of the 1920s. In the early 1930s, Twining was employed as a commercial artist in South Egremont; however, in 1933 and 1934, she was awarded consecutive Tiffany Foundation scholarships, which allowed her to live in New York and focus on creating her own art.

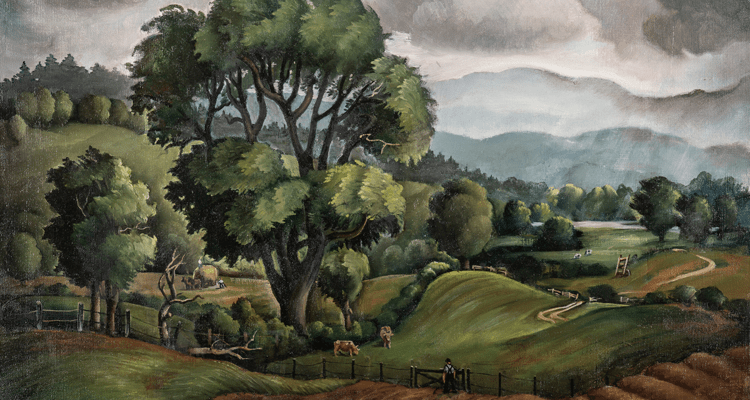

During the Great Depression, Twining returned to Massachusetts to work for the Federal Art Project, a program initiated by the Work Progress Administration (WPA) to provide financial support to artists. Twining worked at least eight hours a day, completing nearly seventy paintings and drawings during the seven years (1935-1942) she was employed by the program. Rendered in her signature hard-edged, realist style, Twining’s WPA paintings primarily consist of urban and rural landscapes, the latter done in South Egremont. She and her mother lived in Boston during the winter and spring, and their summer and fall months were spent in South Egremont, where Twining created many works that depict the village and surrounding farmland, as seen in Rainy Day (pictured above) (1938). Appropriately for this industrious artist, manual labor, a favorite subject for New Dealers, finds its place in Rainy Day—within a bucolic setting of rolling hills and fertile farmland that calls to mind the art of Regionalists like Grant Wood.

Twining’s works were critically acclaimed and featured in many regional and national exhibitions. However, she struggled to find gallery representation once the Federal Art Project ended, and she ended up working as a steel cutter at a General Electric plant. In 1943, she married Irving Humber, and the couple moved to Seattle. Becoming a part of the Seattle arts community, Twining joined the Women Painters of Washington and taught at the Broadway Edison school from 1945 to 1952. In 1946, she was honored with a one-person exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum. Twining initially continued working in her Regionalist style in Seattle, but her awareness of postwar artistic trends led her to begin using looser brushwork and incorporating abstraction in her paintings. She later produced watercolors and studied Sumi-e painting, a type of East Asian brush painting, in the 1970s. Years later, Twining would return to the solid forms and subjects of Regionalism.

Twining continued to paint into her 90s, and after an eight-decade-long career, she passed away in 2004. Twining is celebrated not only for her critically acclaimed landscape paintings but also for starting the Twining Humber Award, which is presented annually to a woman artist aged 60 or over and living in Washington.

Next, we would like to highlight Loraine Elizabeth Moore (1911-1988), a prominent painter and printmaker that was based in Oklahoma City. In the 1930s, Moore began taking art classes at Stillwater Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Oklahoma State University) under the instruction of department head and nationally recognized printmaker Doel Reed. There, she honed her skills in the challenging print medium of aquatint, a technique for which Reed was well known for mastering. Moore continued her art education with San Francisco-based artist Marian Hartwell and painter and sculptor Xavier Gonzalez. Moore also studied at the Portland Art School in Oregon for two years and had several summer sessions with Reed following her time at OSU. By the 1950s, Moore’s work transitioned from a representational style closely resembling Reed’s to one that featured strong abstract designs, striking color contrasts, and intricate linework.

Moore’s personal wealth from oil allowed her to focus on creating art without having to support herself through other ventures. It also made it possible for her to purchase tools and equipment financially inaccessible to other artists. In the 1950s and early 1960s, she possessed one of the few privately owned printing presses in Oklahoma, which she even loaned to Oklahoma City University. Moore was also was active in the arts community in Oklahoma City. She was close friends with Nan Sheets, an influential figure in the Oklahoma City art community and the first director of what is now OKCMOA. Additionally, Moore regularly took part in Oklahoma City’s annual arts festival and appeared twice on Creative Crafts, a local television series focused on the arts.

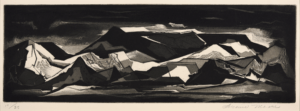

Over the course of more than fifty years, Moore drew inspiration from both her life in Oklahoma and her frequent travels. As illustrated in a large number of her works, Moore frequently traveled to New Mexico, along with places like England and China. Awarded the Titche-Goettinger Company Prize in the first Dallas National Print Exhibition in 1953, Espanol Valley is one of Moore’s many depictions of New Mexico. As seen in the rich black, gray, and stark white angular shapes of this mountainous landscape, Moore was adept at producing striking contrasts and a wide range of tones in her prints. In order to create the linework and rich blacks and grays of Espanol Valley, Moore used etching and aquatint processes. Etching is a printmaking technique that uses chemical action to produce incised lines in a metal printing plate, which then hold the applied ink and form the image. Aquatint is a process in which a resin-treated plate is submerged in acid, creating sunken areas that hold the ink with different degrees of intensity, producing a wide range of tonal values in the resulting image.

Although often remembered as a master printmaker, Moore excelled in a variety of other media, including oil and watercolor. She continued to produce work until her death in 1988. She had a prolific and extremely successful career throughout her life, receiving numerous awards for her paintings and prints and exhibiting at renowned institutions like the National Academy of Design and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The third artist we would like to highlight is Anne Truitt (1921-2004), whose work The Sea, The Sea (2003) is on view in our exhibition Postwar Abstraction: Variations. Truitt is best known for her vertical, wooden sculptures that are meticulously covered with layers of saturated color.

Born in Baltimore in 1921, Truitt grew up in Easton, Maryland, and Asheville, North Carolina. After graduating from Bryn Mawr College in 1943 with a degree in psychology, Truitt soon turned to art. She married in 1947 and enrolled at Washington, DC’s Institute of Contemporary Art the following year. There, she met painter Kenneth Noland, who became a lifelong friend. In the early 1960s, Truitt developed her signature style—colorful wooden columnar sculptures, which blur the line between two and three dimensions. Her first solo exhibition, at Andre Emmerich Gallery in New York in 1963, launched a career that included exhibitions at major museums and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and National Endowment for the Arts, among other accolades. Truitt also published a trio of autobiographical texts entitled Daybook, Turn, and Prospect, in which she explored her experiences as an artist, teacher, daughter, and mother.

Art historians and critics have often linked Truitt’s sculptures to Minimalism and the Washington Color School, although she resisted such labels. While she paid a great deal of attention to color, like many Washington Color painters, Truitt’s hallmark columns are explorations of color in three dimensions, rather than on canvas. Minimalist works, for the most part, are created in series, industrially produced, and geometric. They are simplified in form, and when color is used, it is done so sparingly. Truitt did not embrace the Minimalist aesthetic to the extent that her contemporaries did. Although she had her wooden columns fabricated, Truitt hand-painted directly on these columns, rather than using spray paint or an airbrush, and later in her career, she turned to more polychromatic sculpture. By doing this, Truitt distinguished her work from the barren, mechanical look of Minimalist sculptures. As she explained, “I have been flooded with color on the inside, drab on the outside.” (Truitt, Anne, Daybook, the journal of an artist, New York: Scribner, October 2013.p.228)

Truitt’s works often dealt with personal memory. The physical dimensions of The Sea, The Sea corresponds to the human body in its verticality and resembles architectural elements from Truitt’s childhood on the Eastern Shore in Maryland. Set on a slightly recessed base, The Sea, The Sea, appears to hover just above the floor as if defying gravity. Although The Sea, The Sea’s verticality is bodily, its spare geometry never duplicates the human. Unlike typical horizontal representations of the sea and water in the visual arts, this piece translates the horizontality of the sea and its depth into a vertical section of water beneath a white horizon. This entails yet another departure from Minimalism’s refusal to represent something beyond itself. Here, though, by virtue of the title, The Sea, The Sea invites us to a concentration of nature and our own experience of it.

The last artist we would like to highlight is Karen LaMonte (b. 1967), whose work Chado (2010) is featured in our exhibition Postwar Sculpture. LaMonte is a Czech-Republic-based American artist whose works include sculpture, drawing, prints, and site-specific installations. She typically uses cast glass, metal, clay, or more recently marble to create sculptures of clothing (as well as clouds in her recent series Cumulus, 2017) that retain the sense of movement and drapery as if someone were wearing them.

LaMonte was born and raised in Manhattan, New York. In 1990, following her graduation from the Rhode Island School of Design, LaMonte, who initially created relatively small-scale blown glass sculpture, sought the means to create large-scale sculptures in glass. In pursuit of this ambition, LaMonte traveled to Prague in 1999 on a Fulbright scholarship to work in world-class Czech glass-casting workshops. During her year there, she made her first life-size work, Vestige (2000), a glass dress that suggests an absent wearer by revealing the form of a body. LaMonte then established her permanent studio in Prague and created her first major body of work, Absence Adorned, in the early 2000s. Composed of the same clear glass as Vestige and Chado, these works were made in a similar spirit, exploring the relationship between outer appearance or public character of the body and the more intimate and private characteristics of a person. The works from this stage of her career emphasize the details of lavish, translucent garments, what LaMonte refers to as “social skins,” draped on female figures. In a way, these sculptures are reversals of the Euro-American artistic traditions of portraying the female nude, subverting the tradition of depicting nudes by removing the solid nude and leaving behind a hollow dress.

In 2006, the Japan United States Friendship Commission awarded LaMonte a seven-month fellowship to study in Kyoto, Japan. In 2007, she immersed herself in Japanese culture. She studied the art of kimono making and began to create kimono figures using a variety of materials. This trip inspired her Floating World series, titled after scenes in Ukiyo-e woodblock prints. Chado is part of this series and emphasizes the Japanese garment’s texture and shape. Each piece in the series illustrates the beauty of the kimono and its importance to Japanese culture, while stressing the absence of the female body. Chado (named for the Japanese tea ceremony) hugs the invisible female form, falling over narrow feminine shoulders and cinched just beneath the breasts. Chado is a work of both cultural and female identity that nonetheless removes the body in an act of de-objectification. LaMonte’s practice addresses themes of beauty and loss using clothing to explore the intricacies of the human condition.

LaMonte has spent her career exploring how clothing and materials cover the human body and how those materials can communicate cultural identity. Today, she continues to make art that investigates themes of presence and absence, beauty and ephemerality, through material and the physicality of the human body and its environment.

For more on these artists see:

- Yvonne Twining Humber: Reflections on the Artist on the Centenary of her Birth, Claudia J. Bach talk transcript

- Baerny, Sharon Long. 1995. “Yvonne Twining Humber: an artist of the depression era”. Woman’s Art Journal. 16-23.

- Moore, Loraine Elizabeth, Teresa Kilmer, Kimberly Morton, Sarah Pons, Jessica Provencher, Michelle Rinard, and Louise Siddons. 2015. Between Reality and Imagination: The Works of Loraine Moore. Stillwater, OK: Oklahoma State University.

- annetruitt.org

- Baca, Miguel de. 2016. Memory work: Anne Truitt and sculpture. Oakland, Calif: Univ. of California Press.

- karenlamonte.com

- LaMonte, Karen, and Laura Addison. 2013. Karen LaMonte: floating world. Art Works Publishing.

Credits: Yvonne Twining (American, 1907–2004) Rainy Day, 1938, Oil on canvas, 22 x 28 in. Oklahoma City Museum of Art, WPA Collection, 1942.036. Loraine Moore (American, 1911–1988) Espanol Valley, no date, Aquatint, 9 7/16 x 20 in. (sheet). Oklahoma City Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Robert A. Lively, 1954.001. Anne Truitt (American, 1921–2004) The Sea, The Sea, 2003, Acrylic on wood, 81 x 8 x 8 in. Oklahoma City Museum of Art, Museum purchase with funds provided by the Kirkpatrick Family Fund and Kirkpatrick Foundation in memory of Joan Kirkpatrick, 2010.026. Karen LaMonte (American, b. 1967) Chado, 2010, Cast glass, 39 x 33 x 37 in. Oklahoma City Museum of Art, Museum purchase from the Beaux Arts Society Fund for Acquisitions, 2012.002.