What separates cinema from television? That seemingly fundamental question has become more and more difficult to answer: commercial-free “quality” television is increasingly prominent; auteur-based filmmaking (such as last year’s release of The Irishman) has migrated onto streaming platforms; and now, we only watch movies from home using the same technology we use to watch TV. In other words, if cinema still exists in this exact moment, completely outside of the theatrical experience, then there is something else that separates these two categories—and something, we would add, that we are not going to answer sufficiently in this post.

What we can say is that it has nothing to do, likewise, with the matter of length or even the presence of individual episodes. Speaking of the former first, episodic, long-form cinema dates from at least the 1910’s, when French director Louis Feuillade made a series of briskly-paced, cliffhanger-dependent serials, such as his ten-part masterpiece, Les Vampires (1915-16; available to screen on Kanopy), about a sinister crime syndicate of the same name. Les Vampires was shot under French World War I-era restrictions that prohibited filmmakers from shooting in the streets—though theaters did remain open to exhibit films like the nearly 500-minute-total Les Vampires. Television didn’t yet exist, but its precursor certainly did.

In the decades to follow Feuillade, movies of extreme length remained a holy grail for many filmmakers and cinephiles alike. Erich von Stroheim’s first cut of his classic Greed (1924), for example, ran to over nine hours. (Sorry, readers, but that cut doesn’t exist on Kanopy, Netflix or anywhere else.) Even longer at nearly thirteen hours, Jacques Rivette’s Out 1: Noli mi tangere (1971), which screened over four evenings at OKCMOA a few years back, features a number of the French New Wave’s most famous faces, improvising a conspiratorial scenario across the streets of post-1968 Paris. One of the most film-literate directors who ever lived, Rivette creates a long-form cinema that liberally quotes Feuillade here and elsewhere. However, in the hands of the New Wave master, this form becomes something radically new; it is a massive modernist fiction that, in the filmmaker’s own words, “swallows everything up and then self-destructs.” Beginning in June, Film Society members will be able to watch all four parts of this monumental achievement as part of their three-month free trial of MUBI.

Perhaps the closest recent equivalent to Out 1, Argentine director Mariano Llinás’s fourteen-hour theatrical epic La Flor (2018) divides its narrative into six episodes, with each adopting a different genre, and most featuring the same set of four actresses. Like Rivette’s masterpiece, this major work of recent cinematic fiction—which likewise played over four days of OKCMOA screenings, last year—is a film about making films, a work that tests the outer limits of what’s possible in cinema. Available to stream directly from distributor Grasshopper Film, it is a film, again like Out 1, to be binged as you would Tiger King or Ozark, albeit with your cellphone, tablet and any other screen distraction muted and out of reach. If there is a meaningful difference between television and cinema, perhaps this is it: one is designed to be viewed in an environment of distraction and the other in a space where these aspects of every day life are rightfully forbidden.

Forty-five years before David Lynch provocatively blurred the boundaries between cinema and television with his experimental magnum opus Twin Peaks: The Return—voted “Best Film of the Decade” by the venerable French film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma—wildly prolific New German Cinema master Rainer Werner Fassbinder elevated the mini-series to the level of high art with 1972’s Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day. Commissioned for West German television, the five-episode series, which screened in a new restoration at OKCMOA in 2018, follows young toolmaker Jochen (Gottfried John), his girlfriend Marion (Hanna Schygulla), his eccentric nuclear family, and his fellow factory workers, as they band together and attempt to improve their working and living conditions.

Created in in the wake of Fassbinder’s transformative early-70s encounter with the Hollywood films of Douglas Sirk, Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day combines an effortlessly watchable, if unusually optimistic, multi-strand narrative with Fassbinder’s characteristically virtuosic, melodrama-inspired film style. Eight years later, and only two years before his death at the age of thirty-six, Fassbinder returned to television with the thirteen-episode series, Berlin Alexanderplatz, a magisterial fifteen-hour adaptation of Alfred Döblin’s seminal 1929 novel of the same name. Widely regarded as Fassbinder’s masterpiece, Berlin Alexanderplatz is an intensely immersive, monumental, hyper-stylized portrait of ex-convict Franz Biberkopf, who attempts to reform his ways against the corrupt and chaotic landscape of Weimar-era Germany. (Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day and Berlin Alexanderplatz are both available to screen with a Criterion Chanel subscription.)

More on this week’s epic streaming recommendations:

READ: “How Jacques Rivette’s ‘Out 1’ Invented Binge-Watching,” by Sam Adams, IndieWire

***

Opening this week in OKCMOA’s virtual theater are two more super-sized cinematic masterworks that take their own distinct places along the film-television spectrum. Happy Hour and Sátántangó both enjoyed single-day runs in OKCMOA’s Noble Theater, and while we believe that they are best experienced in a theatrical setting, our current shelter-in-place era feels like the perfect time to settle in with a binge worthy work of art.

From a narrative point of view, Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s (Asako I & II) universally acclaimed drama Happy Hour—which currently holds the distinction of being the longest Japanese movie of all time—has a lot in common with HBO shows like Girls and Sex in the City. Set in and around Kobe, Japan, the film follows four thirty-somethings with diverse goals and personalities as they navigate career setbacks, divorce and the ups-and-downs of long-term friendship. Much like its televisual counterparts, Happy Hour is relatable, charming and compulsively watchable, but Hamaguchi’s film diverges from both TV and commercial cinema in its its fine-grained, novelistic focus on the everyday details of women’s lives, and its audacious embrace of unbroken duration.

Developed out of an improvisational theater workshop led by the film’s now forty-one-year-old director, Happy Hour, much like La Flor, builds itself around a quartet of actresses—in this case non-professionals—who shared the Locarno Film Festival’s Best Actress Prize for their psychologically complex and nuanced portrayals. A number of Happy Hour’s longest sequences revolve around workshops organized by Fumi, who runs a local art-space. Much like the extensive rehearsal sequences in Rivette’s Out 1, these real-time improvisations point back to the film’s theatrical origins, while creating a radical change in tempo that exerts a hypnotic pull on the viewer.

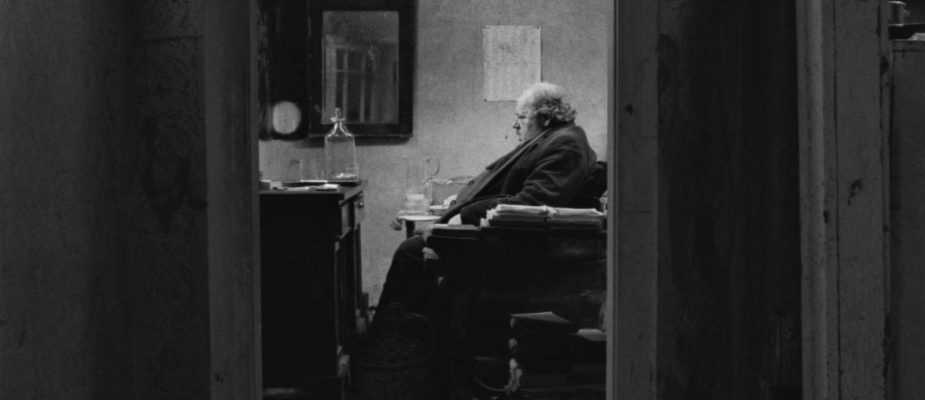

Taking slow-cinema to it’s furthest logical extreme, Sátántangó exists in a rarefied realm of pure cinema. Long regarded as both a holy grail and a litmus test for extreme cinephiles, Tarr’s 1994 masterpiece—meticulously restored by Arbelos Films in honor of its 25th anniversary—was voted one of the fifty best films of all time in the most recent iteration of the prestigious Sight & Sound poll. Based loosely on a 1985 novel of the same name, Sátántangó follows the hard-bitten members of a shuttered collective farm, who plot to escape their small Hungarian village after receiving their final wages. Shot on richly textured 35mm black-and-white stock, the film is composed from a series of twelve, non-linear vignettes and features uninterrupted shots more than ten minutes in length.

While there’s nothing televisual about Béla Tarr’s utterly singular portrait of slow-motion post-Soviet collapse, its closest TV analogue might be the lulling, multi-hour train journeys that gained world-wide cult status for the Norwegian Broadcast Corporation. But rather than inducing serene contemplation, Sátántangó’s extreme adventures in duration seem designed to draw attention to the material conditions of mortal life. Watching these bleakly beautiful, often nearly motionless images unfurl before us, we become aware of ourselves in the act of watching—our blinking eyes, our breath, our restless twitches and our racing thoughts. A film of wry pessimism and towering intellectual ambition, Sátántangó forces us to confront our physical limits and our personal limitations, our fundamental smallness relative to the universe we inhabit. Give Béla Tarr seven-and-a-half hours and he will show you the human condition. Not a bad trade in our book.

-Co-written by Lisa K. Broad & Michael J. Anderson

More on this week’s virtual new releases:

READ: “Béla Tarr’s 10 Favorite Films,” by Leonard Pearce, The Film Stage