Contemplation, ca. 1940

Oil on canvas

Gift of the Estate of Lela O’Toole, 1995.008

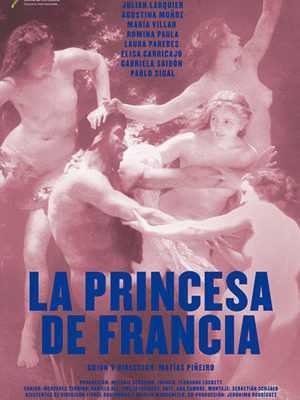

There’s a moment early in this Thursday’s superlative seventy-minute Shakespeare update, The Princess of France (Matías Piñeiro, 2014), that deftly captures the approach of the Museum’s new original exhibition, Posed & Composed: Portraits of Women from the Permanent Collection: Victor, a twenty-something actor, and a pair of female companions, tour the Museum of Fine Arts, Buenos Aires after visiting hours. Moving from room to room, the trio are almost completely surrounded by nudes, busts, and shoulder-up portraits of female sitters, representing an array of periods from the sixteenth to the early twentieth centuries. Arriving at Manet’s Surprised Nymph (1861), Victor confesses to liking this particular portrait more, observing that though “uglier” than his girlfriend Natalia, the sitter nonetheless shares the same gesture—her right hand presses against and cups her bare left arm (see the film still below).

In Posed & Composed, our own twentieth-century American version of what viewers are treated to in this scene from The Princess of France, the gesture is the thing when considering the orientation of the gallery, as is the pose, the composition, the palette and the subject matter—just not a more traditional art-historical chronology. Each of the twelve pieces, by eleven American-based artists, find their places on the wall thanks to the aforementioned commonalities: Walt Kuhn’s Tiger Trainer (1932) and Larry Rivers’s At Z Beach (1982) flank one another as a result of their similar upright, cross-legged pose; Everett Shinn’s Ballerina (1911-2) and Moses Soyer’s Dancers Resting (n.d.; post-WWII) partake in the same profession; Will Barnet’s Reclining Woman (1978) and Doel Reed’s Contemplation (ca. 1940) share a corner thanks to the propped up arms that the respective subjects rest their heads against—and the trees and branches that divide the foregrounds from backs; and the Reed likewise hangs beside another double-portrait of seated women, Leon Kroll’s Composition in Two Figures (1958), looking in different directions.

The point is to encourage a more active form of looking and a more adventuresome consideration of form, to invite comparisons across historical, stylistic and ideological gaps (that minimally will confirm the continued vitality and flexibility of the woman as artistic subject, extending the film’s examples into and past the abstract expressionist moment). Though this might encourage qualitative judgement—like Victor’s uglier Manet—it can also serve to make the work fresh and new, and perhaps to add interest beyond what a more conventional hanging might accomplish (see for instance the exhibition’s mid-1970s Donald Kamihira, and the multiple dialogues it opens up, from the Kroll to the Barnett to Alex Katz’s Jane, 1965). Truly, the most salient advice I can give is to move around the gallery, to search for new vantages that will bring into view multiple works, each with their own visual relationships. And of course, to spend time looking, to mentally catalog the variety of strokes employed by Kuhn, say, for his marvelous circus-themed piece, a real and rarely seen highlight of the permanent collection, or to consider the why behind Rivers’s literal defacing of his seated subject—as she mirrors the Philip Pearlstein on the opposing wall. Posed & Composed opens this Thursday, July 23 at 5:00 p.m.

***

Back to Piñeiro’s The Princess of France (screening Thurs., July 23 @ 7:30 & 9 p.m.), the latest Shakespearean riff, following Viola (2012), by the under-40 Argentine auteur. The briskly paced, yet still exquisitely loose featurette opens on a voice-off radio broadcast, before moving, with music continuing, to a towering overhead of a football match; the latter, a wordless, extended visual gag, builds toward one side amassing and then rushing the opposing net-minder. In no way connected to the film’s Shakespearean subject, Piñeiro’s prologue prefigures instead, and very obliquely, the over-matched romantic geometry that will find Victor overwhelmed by his many partner-actresses (and predicts, likewise, the second painting that more concretely establishes this same man among many women theme).

Following the film’s female goaltender, the camera and the narrative, in this ode to fluidity, will then travel to and join the film’s production of Love’s Labour’s Lost, where we are first introduced to Victor, the romantically unfaithful Guillermo, and the many young women who encircle the film’s two male players—and pass, again very fluidly, in and out of the narrative. (Do pay attention to the opening credits, which identify the names and roles of certain characters; The Princess of France moves fast enough that it can be difficult to keep track.) Piñeiro, in his first of two productions of the play, opts for the backstage, capturing his actors and especially actresses on the edges of the stage and their roles. When the play is subsequently reproduced for the radio, something that will happen after Victor’s one year absence (a plot-point borrowed from the play), Guillermo will take on the role of the Princess, thereby revising the gender-division of the original—with the film’s actresses taking on the roles of his suitors. There is, in other words, an additional, gender-based fluidity at play in The Princess of France, one that destabilizes the original’s emphasis on masculine desire.

Of course, some mention should also be made of the decision to produce Shakespeare, in Spanish, for the radio. A contemporary and avant-garde gesture to be sure, especially when also considers the hip-hop-style scoring that is used for the play’s production, this choice also reaffirms both a fundamental difference of film from theatre, and also one of the thematic keys to the play in consideration. To the former, it is imperative to note that film, like radio, is a recorded rather than performed medium. Unlike in theatre, we never share the same space (and time) of the actors in the performance. As for its connection to Love’s Labour’s Lost, it is well worth noting that this is a comedy best remembered for its language, its wordplay and puns. In this sense, the radio program becomes a sort of distillation of the original’s essence, as pure language—albeit in a language other than its original English; in other words this is a words-only Shakespeare without any of Shakespeare’s words (save for those of us reading the English subtitles).

Regardless, the conceptually dense and deeply pleasurable The Princess of France is truly one of the year’s can’t-miss art films—and the perfect compliment to this Thursday’s Posed & Composed opening. Just be sure to pay attention during the film’s opening credits… or plan on seeing this Argentinian gem a second time, which you’ll probably wish to in any case.

This week’s other Oklahoma City premiere—the pleasure-filled Gemma Bovery will also be returning for two encore shows (Fri., July 24 @ 5:30 p.m. & Sat., July 25 @ 8 p.m.)—is Hiromasa Yonebayashi’s When Marnie Was There (2014; screening Fri., July 24-26 & Thurs., July 30*), purportedly the final film to be made by Japan’s Studio Ghibli (of Spirited Away fame). I won’t go into too great of detail here, except to say that Yonebayashi’s gracefully hand-drawn latest is the second major animated work of the summer (following the marvelous Inside Out) to seriously consider the subject of adolescent depression, while focusing on a young female heroine. If this is to be Studio Ghibli’s last—and, no doubt, we all hope this isn’t the case—the Japanese animation juggernaut will have gone out with a work of real psychological complexity that moves toward a powerful emotional payoff. Inspired quite concretely by Alfred Hitchcock (and especially Vertigo and the film’s namesake Marnie), When Marnie Was There, to use the terms of the weekend, is a genuinely affecting portrait of a young woman, and of the transformative value of female friendship.

*Please note: When Marnie Was There screens Friday and the following Thursday, at 8 p.m. and 7:30 p.m. respectively, in Japanese with English subtitles; and on Saturday and Sunday, at 5:30 p.m. and 2 p.m., dubbed in English.