This week at the Oklahoma City Museum of Art marks the arrival of the stunning My Generation: Young Chinese Artists, the first U.S. exhibition dedicated solely to Mainland artists born in the post-Mao era. Curated by New York-based critic Barbara Pollack, and organized by the Tampa Museum of Art and Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, OKCMOA will be the only venue to show the exhibition in its (near) totality, and will be the final stop before the works return to their native China. Next week, I will have much more to say about the sizable and smartly curated video-art portion of the exhibition. For now, let me simply offer that there indeed is very credible video art coming from twenty- and thirty-something’s in the People’s Republic.

The OKCMOA Film Program will be celebrating the coming of My Generation with our selection of four recent Sinophone features, including two directed by post-Mao Mainland artists: Xu Huijing’s (b.: 1984) Mothers (2013; screening Saturday, Oct. 25 at 5:30 p.m.), a candid and captivating piece of cinéma verité filmmaking that sheds light on the scandalous practice of forced female sterilization; and Liu Jiayin’s (b.: 1981) minimalist, experimental masterpiece Oxhide II (2009; screening Sunday, Oct. 26 at 2 p.m.), a subtly and sophisticatedly choreographed long-take treatment of the filmmaker-daughter and her two parents making dumplings. Both works address key issues and/or undercurrents for My Generation, whether it is the one-child policy of Mothers, or the generational interrelationship of Liu’s fiction-documentary hybrid (which echoes a topic explored in the exhibition’s “Family Ties” section). Oxhide II is also the product of a major new female filmmaking voice in China; it will be introduced by N.Y.U. Cinema Studies Ph.D. candidate Lisa K. Broad (who, along with yours truly, has written about the film here); and will be accompanied by a very appropriate free catered snack following the screening.

This weekend’s other two features come courtesy of two of the greatest living Sinophone directors, Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs (2013; screening Thursday, Oct. 23 at 7:30 p.m. and Saturday, Oct. 25 at 8 p.m.) and Jia Zhangke’s A Touch of Sin (2013; screening Friday, Oct. 24 at 8 p.m.). The latter, which won best screenplay at Cannes 2013, provides a remarkably comprehensive and detailed snapshot of China’s cultural and economic present, as the movie moves in overlapping sections from the Mainland’s snowy north to its subtropical south. Consider A Touch of Sin a more overtly critical context for My Generation, from an internationally acclaimed director who is at least a half-decade older than anyone participating in the exhibition. (For a more extensive analysis of the great A Touch of Sin, one of last year’s very best, please see my review following the film’s premiere at the 36 Starz Denver Film Festival.)

***

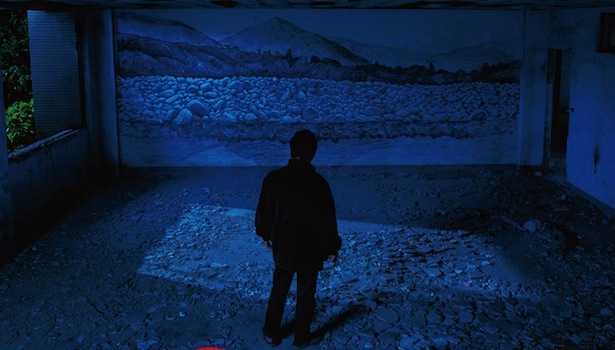

Tsai’s Stray Dogs (pictured) has no real meaningful connection with My Generation, being that it is a (Chinese-language) Taiwanese production directed and co-written by the Malaysian-born, fifty-something auteur of Vive l’Amour (1994) and What Time Is It There? (2001). And truth be told, the film’s programming this weekend is more coincidental than not. However, with video art about to play a disproportionately large and perhaps even unprecedented role at OKCMOA, it is a happy coincidence to the extent that Stray Dogs stands somewhere between gallery practice and conventional narrative cinema. For the uninitiated, the director’s more recent slow cinema has as much in common with how we traditionally consume abstract objects in the museum setting than with how we tend to passively watch narrative films. This is to say that though there is a story in Stray Dogs, the moment-to-moment experience of the narrative ultimately may feel more like the searching act of looking at a painting – which is exactly how the film ends. (To make an OKCMOA analogy, this is the cinematic equivalent of the Washington Color School, not nineteenth century realism or Dale Chihuly.)

Tsai sets the template immediately, providing, in the first of the film’s exquisite (and exquisitely slow) one-take sequence-shots, a formally re-focused emphasis on patient observation, on a multi-sensory exploration of the decomposing interior space – which will lend the sudden kick of a sleeping child something approaching narrative significance. Unfolding over a matter of minutes rather than the seconds that a similar shot would cover even in more conventional art-house fare, Stray Dogs may require extraordinary patience – but it also teaches a more aesthetically alive form of spectatorship, one that invites its viewer to see more and to hear more over the course of its excessively long digital takes. Though there may not be much to process in terms of plot, the visual and auditory richness, not to mention the conceptual complexity and novelty will provide the viewer much to consider amid the film’s considerable moments of dead-time.

In its subject matter, not to mention in its aggressively anti-commercial storytelling form, Stray Dogs exists mainly on the extreme, almost hyperbolic margins of twenty-first century capitalism. It is a film that concerns itself foremost with the meager, mundane existence of a single father (Tsai staple Lee Kang-sheng) and his two school-age children. Depicting their daily struggle to satisfy even their most basic needs, from the shelter they find in a grim single-room space to the grimy public lavatory where they brush their teeth and wash their feet – in the trickle that escapes from the bathroom plumbing – Tsai paints a portrait of subsistence on society’s most distant margins. This is life at its absolutely least glamorous, as it is seen in a series of quotidian, everyday activities and acts of biological necessity (eating, sleeping, urinating – all in view of the camera) that together provide a picture of what life on the outermost edges entails. Here again, the viewer is asked to see more than she or he is typically accustomed in cinema.

As befits this subject, which is to say as is appropriate for characters who struggle to maintain without any hope of economic advancement or personal progress, Stray Dogs proves a comparatively static experience, for most of its two-hour plus running time at least. This will change, at least momentarily, following the film’s most memorable (and certainly discussed) set-piece: Lee’s violent, inebriated, psychoanalytically ripe fondling and consumption of his daughter’s toy cabbage head – a cousin as it were to The Wayward Cloud’s (2005) even more shocking watermelon set-piece. Following this outpouring of abject despair, Tsai will momentarily break from the everyday, as the film’s central patriarch leads his children to the water’s edge, in the midst of precipitous nocturnal downpour. Melodrama, in other words, will make a brief but impactful cameo amid the film’s carefully cultivated banality.

What all of this amounts to, beyond providing one of the year’s most complete reinventions of film language and grammar, is an exceptionally rigorous study of physical presence, of the spatialized experience of time that stands at the very core of film’s spatio-temporal specificity. Or, to put it another way, Stray Dogs is all about the occupation of spaces, whether it is lightly surreal urban architecture that provides the film with its indelible, post-deluge setting – Tsai expressly personifies these places – or the exceptionally marginal edge of the market economy where the film’s protagonists live their unerringly difficult lives. It is here, on the margins of everything, that Tsai is reinventing one art in the image of another.