Over the next two Thursdays, Museum Film will be presenting a pair of 19th-century historical epics by the great Max Ophüls, best known today for his lavish romances, made in both Hollywood and Western Europe (cf. Madame de…, 1953), during the first post-World War II decade. Ophüls was born Max Oppenheimer in Saarbrücken, in western Germany, in 1902. When he began work in the theatre in 1919, he took the stage name Ophüls in order to save his well-to-do Jewish family embarrassment. After moving to Hollywood following Germany’s Occupation of France, following stopovers in Switzerland and Italy, Max dropped the ‘h’ and umlaut from his last name, presumably to de-Germanify in his (temporary) adopted home. Ophüls, or Opuls, as he is credited in the very great Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948, United States), was both geographically and linguistically a filmmaker without a stable national home throughout much of his professional career, beginning long before the shock of World War II, in fact–but not, of course, before Hitler: he left Germany to make La Signora di tutti (1934), one of his best and most stylistically inventive films, in Italy, before moving on to the Netherlands (Komedie om geld, 1936) and then France (beginning with Yoshiwara, 1937, which featured Japanese actors and was originally intended to be shot in Japan).

Over the next two Thursdays, Museum Film will be presenting a pair of 19th-century historical epics by the great Max Ophüls, best known today for his lavish romances, made in both Hollywood and Western Europe (cf. Madame de…, 1953), during the first post-World War II decade. Ophüls was born Max Oppenheimer in Saarbrücken, in western Germany, in 1902. When he began work in the theatre in 1919, he took the stage name Ophüls in order to save his well-to-do Jewish family embarrassment. After moving to Hollywood following Germany’s Occupation of France, following stopovers in Switzerland and Italy, Max dropped the ‘h’ and umlaut from his last name, presumably to de-Germanify in his (temporary) adopted home. Ophüls, or Opuls, as he is credited in the very great Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948, United States), was both geographically and linguistically a filmmaker without a stable national home throughout much of his professional career, beginning long before the shock of World War II, in fact–but not, of course, before Hitler: he left Germany to make La Signora di tutti (1934), one of his best and most stylistically inventive films, in Italy, before moving on to the Netherlands (Komedie om geld, 1936) and then France (beginning with Yoshiwara, 1937, which featured Japanese actors and was originally intended to be shot in Japan).

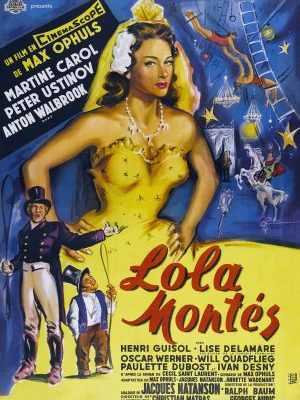

The first of Museum Film’s two 35mm screenings, in an exceedingly beautiful brand new print that debuted in New York just this past March, is the director’s long-neglected From Mayerling to Sarajevo (1940; screens Thursday, May 14 @ 7:30 p.m. only), made on the eve of the Second World War, with a title that speaks to the director’s itinerant experience of Europe during the rise of Nazism–and one that prefigures his continued rootlessness in the decade and a half to follow (Ophüls died back “home” in Hamburg in 1957). As the title suggests, this is a film about Europe and its troubled late 19th and early 20th century history: in word, the film begins with the murder-suicide of one monarch and ends with the assassination of another, a murder that would lead to the outbreak of World War I. It is also a film about the closing of a dynastic line that comes about as a result of a morganatic marriage. In this sense, From Mayerling to Sarajevo is an early example of Ophüls’ dissection of the romantic ideal, an ethos that would receive its most spectacular deconstruction in the late, great Lola Montès (1955, West Germany/France; screens Thurs. May 21 @ 7:30 p.m. only), the second of Museum Film’s two-picture tribute to Ophüls. That is, by pursuing love at the expense of all else, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand (played here by John Lodge, notable for his work in June’s The Scarlet Empress, and more so for his later service as a US ambassador and the Governor of Connecticut), helps to precipitate the end of the House of Hapsburg within the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

A quick, non-film, but related OKCMOA note: next month, the Museum will welcome Dr. Géza von Habsburg, Archduke of Austria and great-great grandson of Emperor Franz Josef, the villain as it were in From Mayerling to Sarajevo. Dr. Habsburg will be lecturing on Karl Fabergé, jeweler to the Russian Imperial family and Tsar Nicholas II–who as it happens, attempted to advocate on Franz Ferdinand’s behalf concerning his unsanctioned marriage to a Czech countess. Oh yes, and then there is the Czech identity of the heroine, the Countess Sophie Chotek, played here by Edwige Feuillère–a beauty worthy of destroying an empire over, in the most Ophülsian of sentiments. The point, in pointing out that Feuillère is playing a Czech, is to remind the reader that the remainder of this weekend will be committed to screening the very latest in Czech cinema (with the 2015 Czech That Film Festival). You can’t escape the Hapsburg’s and the Czech’s over the next month or so at OKCMOA–not that anyone would want to.

Come for the Hapsburg’s and the Czech’s, to be sure, but stay for Ophüls’ exquisite mise-en-scène, a visual style of uttermost elegance and adornment, which above all respects the flow and passage of time within some of the most extraordinary long takes that the cinema has ever seen. Yes, Europe’s dissolution and the “explosion of the romantic ego” (to quote one of his greatest admirers, Andrew Sarris, on Lola Montès again) are as always among the director’s subjects, but so is the even more elemental passage of time, a fundamental loss that is built into the medium’s temporal nature. When the director cranes through his gloriously appointed interiors or walks with his briskly moving major and minor players alike, he is affirming, time and again, that time has no end (again echoing Sarris, who wrote so wonderfully on Ophüls), that all things will pass, whether it is an empire or a youthful romance. Ophüls’ tragedies are built out of the very stuff of cinema, passing time–which in the director’s work is generative of his extraordinary, almost unparalleled camera movements. A man without a clear country, Ophüls instead belonged to the cinema itself.