Two days and one Competition film in, and I already have been fortunate enough to see a work that will be certain to number among the crowning achievements of the 65th Berlinale (the Berlin Film Festival). Of course, this work of substantial ‘cinematic’ interest is not the said Competition title, nor is it even a “movie” at all, at least in the words of its maker. It is instead an object of “three dimensional sculpture,” an instillation, in fact, that is being exhibited as part of the Berlinale’s Forum Expanded side program: Canadian avant-garde master Michael Snow’s TAUT (2012). But more on this great work (about cinema and of the cinema, if not of cinema) shortly.

For now, let me begin with day one and that first Competition work, Catalan director Isabel Coixet’s Nobody Wants the Night (2015; pictured above), which was selected as the Berlinale’s opening night film. Let me pause for a moment and apologize to my seasoned festival-going readership for the following anecdote – actually I should probably apologize for my lack of outrage toward Nobody Wants the Night, but I’ll get to that. Having arrived in Berlin on the first day of the festival – and again this is more for the uninitiated, as I certainly was – I arrived too late to acquire tickets for day one. So, on a whim, and with nothing better to do – save perhaps to sleep, which I had managed to do for all of about 90 minutes during the previous 36 hours – I decided to attempt the second of two opening night screenings of Coixet’s film, featuring a re-broadcast of what would turn out to be the hour-long, celebrity (James Franco, Juliette Binoche) and dignitary (Berlin mayor Michael Müller)-studded opening ceremony. My snap decision paid off, somewhat unexpectedly, when I managed to secure the last, yes the last (the ticket-seller put one aside, without even telling me she would, while I ran to an A.T.M.) of the roughly 1,500 tickets sold. Suffice it to say that I was going into Nobody Wants the Night with considerable good will, and even more delirium.

I was also going into Nobody Wants the Night with the reasonable expectation that it was going to be bad on some level – and yes, it was that. After all, this Juliette Binoche vehicle co-stars Japanese star Rinko Kikuchi as the Inuit lover of Arctic explorer Robert Peary, Binoche’s husband in the film. So, with this as a ground, let me just say that I did not despise Nobody Wants the Night, as I can only imagine many did (and most familiar with my tastes would expect that I would). Nodding off, as I did, once or twice, as Binoche crosses the incandescently beautiful Arctic landscapes only helps, or I should say, aids a narrative that is aware of its comparative unreality. If you’re going to see Nobody Wants the Night, see at a great deal less than your best. Perhaps it was the right choice for Opening Night after all.

Then again, one and all might be forgiven for taking seriously a film – and therefore hating said film – that takes itself rather seriously in its feminist critique of the cost to womanhood (for man’s pursuit of his dreams), not to mention for a gratuitous title about the plight of the Inuits to close the picture. Syntactically, Nobody Wants the Night is an object of the frontier, of the site where ‘Eastern’ manners are made to look ridiculous in the face of a savage wilderness, here in both politically incorrect respects. Yes, there’s a lot to hate here, and obviously Coixet’s film should not theoretically be opening a festival of Berlin’s stature – but in my sub-alert state, the work’s occasional visual poetics and its unhinged melodramatics, I did find myself half captivated. High praise I know.

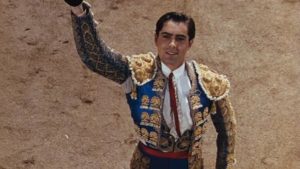

Neither of my two theatrical day two screenings, Tom Sommerlatte’s Summers Downstairs (2015), from the Perspektive Deutsches Kino section, and Rouben Mamoulian’s restored Blood and Sand (1941; pictured), from the Berlinale’s Techicolor Retrospective, require too much attention here. The former, a rather unexceptional, though representative enough piece of early 21st century German cinema (an area of real strength over the past decade in particular), manages an obvious, though still mostly effective sexiness and sense of humor in its story of two very different brothers, who unexpectedly spend their summer together with their dispositionally different French and German significant others. (For a much more successful and ambitions entry into this resurgent national cinema, Museum Films will be playing Dominik Graf’s 2014 Berlinale highlight, and German Best Foreign Language Oscar submission, Beloved Sisters, next month.)

Neither of my two theatrical day two screenings, Tom Sommerlatte’s Summers Downstairs (2015), from the Perspektive Deutsches Kino section, and Rouben Mamoulian’s restored Blood and Sand (1941; pictured), from the Berlinale’s Techicolor Retrospective, require too much attention here. The former, a rather unexceptional, though representative enough piece of early 21st century German cinema (an area of real strength over the past decade in particular), manages an obvious, though still mostly effective sexiness and sense of humor in its story of two very different brothers, who unexpectedly spend their summer together with their dispositionally different French and German significant others. (For a much more successful and ambitions entry into this resurgent national cinema, Museum Films will be playing Dominik Graf’s 2014 Berlinale highlight, and German Best Foreign Language Oscar submission, Beloved Sisters, next month.)

Blood and Sand, on the other hand, and somewhat ironically given its place in the Technicolor program, is essentially ‘white elephant’ art – a work of narrative bloat and an arid sensibility – though this bullfighting A-picture does at least make use of its three-color technology in its representations of an exceedingly flamboyant, object of the beholding female eye, Tyrone Power, and his sexually forthright mistress, Rita Hayworth; or more to the point, in few films has Technicolor been used to better effect in depicting a work’s spectacular costuming. Though Mamoulian had a very short window as a major artist (maybe just two years, 1931-1932), there is at least the historical-aesthetic interest that the Technicolor retrospective teases out in the distended Blood and Sand.

One Competition Film, one Perspektive Deutsches Kino title and one from this year’s Retrospective – and not an unambiguous recommendation in the group. Such as it is, I suppose, in the early stages of a festival when one must take what they can get ticket-wise – or get very lucky (if that’s what you can call it; Blood and Sand was also a hand-written last ticket – maybe I should take these last tickets as an omen in future). Never mind, there again has been one truly extraordinary offering in Snow’s TAUT. Composed of still photographs of protests, the economically fragile and so on, from the Ryerson Image Center, TAUT projects these still photos onto a small screen and over a papered three-by-three chair and desk grid (pictured). In the film that is being projected onto the screen, the wall and the school desks, Snow himself holds each of the aforesaid stills in place, in his visible gloved hands, until he manually switches to another. The possibility of movement that Noël Carroll so famously described in Snow’s work is here present in Snow’s physical labor, in his presence during an act of filmmaking that covers the duration that he is able and willing to hold each of the stills.

One Competition Film, one Perspektive Deutsches Kino title and one from this year’s Retrospective – and not an unambiguous recommendation in the group. Such as it is, I suppose, in the early stages of a festival when one must take what they can get ticket-wise – or get very lucky (if that’s what you can call it; Blood and Sand was also a hand-written last ticket – maybe I should take these last tickets as an omen in future). Never mind, there again has been one truly extraordinary offering in Snow’s TAUT. Composed of still photographs of protests, the economically fragile and so on, from the Ryerson Image Center, TAUT projects these still photos onto a small screen and over a papered three-by-three chair and desk grid (pictured). In the film that is being projected onto the screen, the wall and the school desks, Snow himself holds each of the aforesaid stills in place, in his visible gloved hands, until he manually switches to another. The possibility of movement that Noël Carroll so famously described in Snow’s work is here present in Snow’s physical labor, in his presence during an act of filmmaking that covers the duration that he is able and willing to hold each of the stills.

The effect in part is to transform the photographed image, in its lower sections especially, where it falls onto the covered classroom chairs and desks, into a more abstract field of light and shadow (thus destabilizing its connection to the photographed object). TAUT also brings to the fore the easily overlooked fact of a two-dimensional image’s projection onto a flat screen. Snow instead re-purposes this historically fundamental aspect of cinema-going, transforming the substances of the silent medium (space, time, light and shadow) into a newly three-dimensional form that preserves said substance of cinema, even as it eschews its more representation aspects. In a sense, TAUT is some quite compelling form of pure cinema, all space (even with suggestion of that behind the opaque still), time and light, without perhaps being cinema at all.

Which leads us back to Snow’s insistence that this is not a ‘movie.’ Whether or not we make this determination, TAUT’S great significance resides its ability to make us re-see the art form (in his motionless photographs, held in place by a hand, imperfectly, importantly – rather than the technologies of the camera, the intermittent mechanism and the projector). It encourages us to rethink what we take for granted, making the Wavelength (1966-7) director’s latest a properly pedagogical piece, of semi-cinema, if we can say that, in keeping likewise with its classroom setting (and of course the Leftist thrust of the film’s visual archive). TAUT has an enormous amount to teach its viewer, especially about a medium we think we know, but rarely comprehend in its totality.