In its 48th year of existence, the International Forum of New Cinema, or Forum for short, towered above the rest of the 68th Berlinale. Amidst a Competition that struggled to live up to its high-profile opener, Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs, and a Panorama that failed to see any breakout successes on the scale of last year’s Call Me By Your Name, the 48th Forum debuted a series of works that together suggest the continued health of cinema’s more experimental side. Indeed, of the thirteen that I managed to see, none was without interest—something that certainly cannot be said for the eight Competition titles I viewed—and several were very good or even great. While the Forum may always be the most reliably thought-provoking of Berlin’s many sections, the 48th version still felt like a banner year—especially in the context of the Competition’s conspicuous disappointments (with Lav Diaz’s first crack at the musical, the near-four-hour Season of the Devil, foremost among the letdowns).

Like any catholic showcase of new art cinema, the Forum is resistant to grand narratives. Yet, the 48th incarnation still managed to produce a couple of particularly complementary film pairings, and one sprawling East Asian masterwork, which will go far to define this year’s Berlinale. First up are a set of exceptionally smart and amusing sports documentaries from Europe: Corneliu Porumboiu’s Infinite Football and Julien Faraut’s In the Realm of Perfection. Beginning with the work of the Romanian master Porumboiu (Police, Adjective, The Treasure), Infinite Football is constructed around a series of interviews with the unexpectedly engaging Laurențiu Ginghină, a middle-aged Romanian man who broke his fibula playing soccer in 1986, and his tibia on New Year’s Eve 1987. Following Ginghină’s narration of these still-traumatic events, and of the painful long walk home that he was forced to make after the second injury, Porumboiu’s subject begins to establish the parameters for the reinvention of a sport that he believes to be deeply flawed in its rules and play. With his interlocutor-director appearing on camera with him during their subsequent conversations, Ginghină systematically refines the sport by changing the shape of the pitch, replacing the 90° angled-corners in which he initially injured himself; and by eliminating the forward pass and player movements between zones (an innovation, in this last instance, which seems tailored to Ginghină’s substantially curtailed range of motion). Taken together, Ginghină insists that his interventions will create a faster game, and one that refocuses the sport around its true star, the inanimate ball.

Ginghină’s vision for the sport is far grander, however, than a few changes in the rules initially implies. What Porumboiu’s subject has in mind is nothing short of a new utopia, a novel concept of the world that combats the violence and suffering ingrained not only in Christian society, but also in its language. (In this last sense, Porumboiu returns to one of the key thematic concerns of his 2009 masterpiece, Police, Adjective). As the filmmaker notes, it is a utopia that is Sot in nature, one that deemphasizes the individual and prioritizes teamwork anew in the special importance that it places on passing. At the same time—and appropriately so for the post-Communist cinema of Porumboiu—it is a utopia that is tested and found wanting as it fails to predict the actual behavior of its players, something we will see in practice during the film’s exposition soccer match.

Infinite Football is very much a film about its Romanian country of origin, from its failed Communist experiment to the bureaucratic inefficiencies that have overwhelmed the country in the more than two decades since. Ginghină, for instance, in his day job as government bureaucrat, meets with a mother and son who still have not had their land returned to them in the almost three decades since the Revolution (a fact that Porumboiu seems to find both dumbfounding and humorously typical); the film’s primary subject seems very little interested or willing to help his visitors, though at least Porumboiu’s presence does spur superficial action. Then there is the film’s extraordinary final passage, narrated again by Ginghină’s philosophical speculation. Here, Porumboiu shifts to the country’s gloomy industrial landscape, shifting the film’s focus from individual to nation, even as the film replicates Ginghină’s life-defining New Year’s walk. A moment of poetic grace, this passage’s corresponding verbal eloquence imbues Ginghină with an intellectual dignity that is otherwise lacking in his comically absurd conversations with the bemused director.

A work of the archive rather than the interview, Julien Faraut’s ceaselessly fascinating tennis-themed doc, In the Realm of Perfection, builds its exploration of athletic perfection and cinematic truth around a series of experimental instructional films shot at Paris’s iconic clay-court venue, Roland Garros, during the 1980s. Faraut immediately narrows his focus to the the reels containing John McEnroe, and his legendary bad temper. Shot in order to focus on the play of the individual rather than the back-and-forth of the match, Faraut succeeds first in establishing the particularity of of McEnroe’s non-standard technique by slowing down his 16mm stock: we watch breathlessly as McEnroe hurls his serve far above his head and even further from the baseline, with his body thrusting forward to make contact moments before his feet return to the clay court. We also watch as he waits for his opponent’s serve or their return, always suspecting that McEnroe’s groundstroke is entirely controlled, that he has the power to place the ball at will, even if he does not always succeed in executing thus.

In a very real sense, McEnroe plays himself in these matches, even more than his opponent—a point that is established by the experimental, single-player nature of In the Realm of Perfection’s archival instructional films (as opposed to tennis’s conventional mise en scène, where the location of the ball dictates camera movement). The conventional sports broadcast, when considered in light of In the Realm of Perfection’s archival trove, accordingly becomes an object of falsehood (after Godard’s quote that films lie and sports do not), a distraction from the truth of the player, and especially a player like McEnroe who endeavors to control every aspect of the match, from the gameplay to the sounds of the crowd—including the hum of the 16mm camera—to the judges’ line calls, which time and again he calls into dispute.

Faraut’s film is foremost a portrait of one of the sport’s most singular figures, an extreme perfectionist whose internal character the film seems to extract. It is also an exceptionally effective rumination on the many compelling connections between tennis and cinema, beginning with their shared creation of time (a connection that for Faraut explains iconic French critic Serge Daney’s interest in the game): in both cinema and the racquet sport, and unlike in games such as soccer, which progress over a very specific duration, the participant(s) create the time needed to complete their work, whether it is the three victorious sets of the Roland Garros men’s match, or the time that will unfold before the film’s “Fin” title. In the Realm of Perfection is a film about the authorship of both cinema and sport, made within the only tradition—a philosophically and theoretically minded French art cinema—where such a work seems possible.

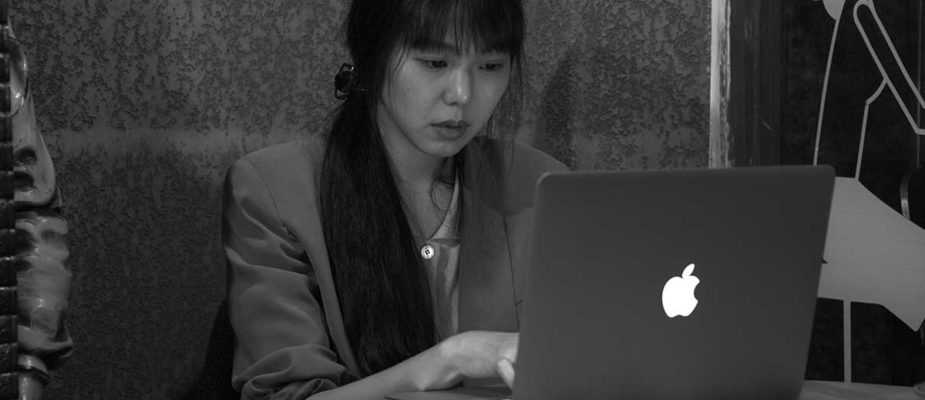

Grass (pictured above), Hong Sangsoo’s fourth feature since the start of last year, and his twenty-first since he last appeared in Forum with The Day a Pig Fell into the Well in 1996, treats the subject of authorship with even greater conspicuity. Set largely in lazy coffee shop, which the off-screen owner scores with his own private classical music soundtrack, Hong’s latest bounces between a series of on-camera conversations, mostly featuring one man and one woman, and a (mostly off-camera) nearby writer, played by latter-day Hong axiom Kim Minhee. Kim may or may not be authoring the film’s various exchanges on her laptop—Hong’s is a cinema that refuses to delineate story-world fact from fiction. The exchanges play out like a series of variations on a single set encounter: the film’s various configurations of characters discuss a suicide or suicide attempt, they broach the topic of artistic collaboration, and frequently an older male character will obliquely proposition a younger woman. Throughout, Hong subtly varies his shooting style, alternating between panning and static two-shots, ones, and later on, an over-the-shoulder staging that makes insistent use of rack-focus—and then, dramatically, shadow. Grass provides a compendium of alternatives for shooting the various ways in which people converse, while seated around tables with coffee and, of course, soju.

Kim will break from the coffee shop setting, traveling with her brother to dine with the latter’s fiancee, midway though the film’s lean sixty-six minute running time. Here, Hong introduces food, drink, and three people into the film’s very mathematical equation, elements that will continue after Kim returns to the cafe at night. This intermediate setting also provides the film’s most idiosyncratic and memorable moment when we repeatedly see a new character ascending and descending a staircase—Duchampian allusion is not new to the director of Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors—in a gesture of pure movement and exaggerated repetition. Doing the same thing time and again: this is the essence of Grass, and of the director’s metronomic art-cinema, a cinema has managed to repeatedly renew itself in feature after feature, despite his works’ immense similarities.

The director’s latest (at the time of this writing only; no doubt there will be at least one more in 2018) is one of his and Kim’s most novel recent efforts, in its organization around a series of conversations, rather than a single character or two. It is a film, again, about the process of creation, of conceiving and then manipulating and transforming various narrative scenarios, inserting new actors and backstories into the same basic template. Grass, much like In the Realm of Perfection, is also an eminently funny and engaging cinematically self-reflexive object, a work that finally invites its lonely creator into its Midsummer world as it builds toward its own, well-earned Shakespearean grace note.

While Grass does not yet have announced US distribution, Oklahoma City readers should take comfort in the fact that Claire’s Camera will become the second of the director’s three 2017 world premieres to play the Museum this coming April—following January’s On the Beach at Night Alone. Nowhere near as frequent and even less regularly distributed in North America are the films of Park Kiyong, best known here for his masterful, early twenty-first century treatment of romantic ennui, Camel(s) (2001). At that time, with Hong only beginning to emerge as a major new world-cinema voice, it seemed plausible to put the two directors on the same level, to think of the talky Korean art cinema as a trend rather than the purview of a single cinematic deity. While we are far past that point today, the 48th Forum did reintroduce Western audiences to the emotionally and aesthetically mature work of Mr. Park with Old Love, a graceful and precise treatment of a romantic re-coupling two-and-a-half decades after the end of a young love affair.

Park’s melodrama opens in an airport, capturing the film’s female lead, Yoonhee (Yoo Jungah) as she travels home from Canada to deal with an ailing parent. There, she crosses paths with Jungsoo (Kim Taehoon), an old flame who is now widowed and dealing with a failed business in their hometown. Over the course of the coming days and weeks, Yoonhee and Jungsoo find escape from their loneliness and melancholy in a series of nostalgic, increasingly romantic meetings that will culminate in a weekend away at a mountain resort. As they progress toward this final excursion, one where we will be confronted by the reasons behind Jungsoo’s decision to quit acting, Park trains his observational, often telephoto camera on his two leads, searching for subterranean meaning in their very carefully rendered gestures and facial expressions, and, poetically, on the places of their past and present. Old Love is a consummately cinematic expression of feeling and geographically alike, a very welcome return for the director of the extraordinary, if largely forgotten Camel(s).

Rounding out this recap of the 48th Berlinale Forum—a section, though it is beyond the scope of this piece, which also produced distinctive original American indie fiction from Ricky D’Ambrose (Notes on an Appearance), Josephine Decker (Madeline’s Madeline), and Ted Fendt (Classical Period)—is one last, instant-classic art-melodrama from Mainland China, Hu Bo’s monumental An Elephant Sitting Still. Clocking in at a massive 230 minutes, Hu’s invigorating feature-film debut, made by the acclaimed twenty-something novelist before he took his own life late last year, follows a despondent set of characters in industrial Northern China as they navigate the consequences of their circumstances and actions. Among those around whom An Elephant Sitting Still is built are Bu (Peng Yuchang), a teenager who is scolded by his parents at home, and later finds himself involved in the accidental death of a gangster’s ne’er-do-well younger brother; his gal-pal Ling (Wang Yuwen), who has forged a friendship with their school’s vice dean—a relationship that will prove humiliating for her and career-ending for him, if discovered; and the aforementioned low-life gangster Cheng (Zhang Yu), whose adulterous actions leads to another’s suicide. Across these, and other more minor storylines, Hu’s Steadicam cinematography unfolds in a series of artfully mobile, shallow-focus long takes that collectively convey the interconnectedness of the character’s disparate, tragic fates.

An Elephant Sitting Still’s achievement resides in the crystalline clarity of the director’s worldview, of an unshakable insistence on the irredeemability of life in contemporary China and beyond, a point of view expressed repeatedly in the dialogue. It also comes across in the film’s bleak interior and exterior settings, in the incidents that structure the narrative, and finally in the range of options that present themselves to the beaten-down heroes. An Elephant Sitting Still resembles nothing so much as A Brighter Summer Day (1991), Edward Yang’s similarly novelistic, equally ambitious, and impossibly accomplished portrait of Taiwanese adolescence set during the director’s own teenage years.

Yet, Hu’s first and last feature feels even more intent on exceeding the precisely realistic than does Yang’s film, as its gangster genre overlay yields an unexpected reprieve for Bu, before the latter, his grandfather and Ling pair up to travel to glimpse the elephant of the film’s title. While their trip will not likely reverse their fates, it will at least suspend them, momentarily, offering a juncture completely outside the film’s despairing world and the narrative alike, as the performers gather to play an impromptu game of hacky sack, in extreme telephoto long shot, on the side of an empty country road. Hu did not allow himself any similar respite in the wake of his first and last masterwork, the film of this year’s Berlinale.